Introduction to Islamic Art - Muslim HeritageMuslim Heritage![]()

![]()

Introduction to Islamic Art

One area where the genius of the Muslim civilisation has been recognised worldwide is that of art. The artists of the Islamic world adapted their creativity to evoke their inner beliefs in a series of abstract forms, producing some amazing works of art. Rejecting the depiction of living forms, these artists progressively established a new style substantially deviating from the Roman and Byzantine art of their time. In the mind of these artists, works of art are very much connected to ways of transmitting the message of Islam rather than the material form used in other cultures. This article briefly examines the meaning and character of art in Islamic culture and explores its main decorative forms-floral, geometrical, and calligraphic. Finally, it looks at the influence of the art developed in the world of Islam on the art of other cultures, particularly that of Europe.

Table of contents

***

Note of the editor

This article was first published in July 2004. It is edited here in HTML, with revision. © FSTC 2004-2010.

***

The art of Islam has attracted the attention of a number of Western scholars

[1] who gained good reputations because of their contributions to the study and publicising of the field. Despite this positive aspect, their work contained an element of prejudice as they repeatedly applied their Western norms and criteria to their evaluation of the art produced in Islamic history. In their views, far from contributing to the arts of its society, Islam has restricted, diminished and undervalued artistic creativity. Islam is seen as obstructive and limiting to artistic talent and its art is often judged by its incapacity to produce figures and natural and dramatic scenes. Such arguments illustrate a serious misperception of Islam and its attitude to art. The view that Islam promotes harsh and simple living and rejects sophistication and comfort is an accusation often made by orientalist academics. This false claim is rejected by both the Qur’an and the example of Prophet Muhammad. The Qur’an, for example, permits comfortable living if it does not lead the believer astray:

“Say, who is there to forbid the beauty which God has brought forth for his servants, and the good things from among the means of sustenance” (Qur’an 7:32).

This message is emphasised again in another verse:

“O you who believe! Do not deprive yourselves of the good things of life which Allah has permitted you, but do not transgress, for Allah does not love those who transgress.” (Qur’an 5:87).

The authentic saying of Prophet Muhammad which was narrated by Al-Boukhari:

“Allah is beautiful and loves beauty.”

This is perhaps the clearest translation of the position of Islam towards art. Beauty, in Islam, is a quality of the divine. The great scholar Al-Ghazali (1058-1128) considered it to be based on two main criteria involving the prefect proportion and the luminosity, encompassing both outer and inner parts of things, animals and humans.

The other determinant factor influencing Western scholars’ views on Islamic art is connected to the Greek-influenced approach which considers the image of man as the source of artistic creativity. Thus, portraits and sculptures of man were seen as the highest work of art. According to this view, man is nature’s most magnificent and most beautiful creature and should be both the start and destination of human artistic endeavour. Successful works of art are those which explore the inner depth and external physical appearance of the human body. Perhaps the highest position given to man, in this art, is when divine beings are represented in his form, or when he is represented as being created in the image of the Deity. Islamic art, however, has a radically different outlook. Here, man is seen as an instrument of divinity created by a supremely powerful Being, Allah.

Byzantine art was fundamentally based on the incorporation of Christian themes into Greek humanism and naturalism. Together, these concepts symbolised and reflected divinity. Man and nature were seen as the image of the divine. This new figurative art was not seeking the aesthetic per se, as in the Greek tradition, but striving to translate concepts in Christian belief such as salvation and sacrifice.

As they do with many fields, Western scholars often relate Islamic art to Greek and Byzantine origins, claiming that the artists of the Muslim world only imitated or borrowed from these two cultures their art and reproduced it in a Muslim “dress” of Arabesque and calligraphy. Byzantine inspiration started in the early stages of the Muslim Caliphate when the Umayyad Caliphs Abd-al-Malik

[2] and Al-Walid I

[3] sent for Byzantine artists to decorate the Dome of the Rock (691-92) and the Great Umayyad Mosque of Damascus (705-714). Byzantine influence is seen in the iconographic themes in the Dome of the Rock, as reflected in the mosaics of crowns and jewels of that mosque, which Grabar (1973) believed were emulating Byzantine symbols of power. These decorations were symbols of holiness, power and sovereignty in Byzantine art. Pursuing this theme, he says:

“In other words, the decoration of the Dome of the Rock witnesses a conscious use by the decorators of this Islamic sanctuary of representations of symbols belonging to the subdued orto the stillactive enemies of Islam” (Grabar 1973, p. 48).

Yet, Grabar later admits that the Arabs, both before and after Islam, used to offer their precious belongings, including crowns, to the Kaabah and hang them there

[4].

In relation to vegetal representations, in Grabar’s view, once again the artists of Islam seem to borrow from Byzantine depictions of heaven as if they lacked any knowledge or literary description of it. He claims that Byzantine art was so complete and superior that the Muslims had to emulate it. Faced with the question of why the Muslims did not adopt figurative art, Grabar argued that they had to give it up due to the superiority of the Byzantine art which they could not compete with. He says that:

“the Umayyads could hardly in one generation acquire the sophisticated practice of imagery which characterised Byzantium. Faced with this dilemma, the Muslims tried both alternatives, but soon discarded imagery, and, as we have seen adopted the techniques of Byzantium without its formulas”.

Grabar clearly disregarded the opposition of Islam to imagery, which is exemplified in a number of the Prophet Muhammad sayings (see below).

Von Grunedaum (1955) provided a more comprehensive view arguing that the lack of imagery was due to the position of man in the Islamic religion. An important aspect of Muslim theology was the prominence of the attributes separating God, the Creator, and man, his favourite creature. Man is guided by and subject to his fate and therefore cannot reach the position of God, which other religions say he can attain. The fundamental principles of art in Islamic culture are the declared truths that there is “no god but God” and “nothing is like unto Him”; His realm is neither space nor time and He is known by ninety nine attributes, including the First and the Last, and the Seen and the Unseen, and the All-Knowing:

Allah! There is no god but He, the Living, the Self-subsisting’ Eternal. No slumber can seize Him nor sleep. His are all things in the heavens and on earth. Who is there that can intercede in His presence except as He permits? He knows what (appears to His creatures) before or after or behind them. Nor shall they compass aught of His knowledge except as He will. His Throne doth extend over the heavens and the earth, and He feels no fatigue in guarding and preserving them for He is the Most High, the Supreme (in glory) (Qur’an2:255).

This is perhaps the main division in the philosophy and approach towards art between the Muslims and non-Muslims. With this approach, Islamic art did not need any figurative representation of these concepts. How can he depict God if he believes that He is the Unseen and nothing is like unto Him? Any artistic expression of these, either in natural or human forms, would undermine the meanings and the essence of the Muslim faith. Consequently, artists engaged in expressing this truth in a sophisticated system of geometric, vegetal and calligraphic patterns (Al-Faruqi, 1973). Islam was the only religion that did not need figurative art and imagery to establish its concepts (Von Grunedaum, 1955).

Like other aspects of Islamic culture, Islamic art was a result of the accumulated knowledge of local environments

[5] and societies, incorporating Arabic, Persian, Mesopotamian and African traditions, in addition to Byzantine inspirations. Islam built on this knowledge and developed its own unique style, inspired by three main elements.

The Qur’an is seen as the first work of art in Islam and its chef-d’oeuvre (Al-Faruqi, 1973). The independence of some verses and the interrelation of others form extraordinary meanings as each verse takes the reader into a unique divine experience feeling its joy and happiness, terror and fearfulness, bliss and anger, and so on. The constant repetition of these experiences in the verses of the Qur’an “winds up consciousness and generates in it a momentum which launches it on a continuation or repetition and infinitum” (Al-Faruqi 1973, p.95). The final outcome of this experience makes the reader feel the presence of God as described in the verse:

“when the verses of the Beneficent are recited unto them, they fall down prostrate in adoration and tears” (Qur’an 19:58).

As a result, artists drew lessons and methods from their experience of the Qur’an, developing a new approach to art characterised by the independence and interdependence of its formative elements. The emphasis was on the presence and attributes of the divine Creator rather than on His creatures, including man. Islam sees all men equal regardless of colour or form (perfect or imperfect). The only distinction between them is made on the basis of their piety. Consequently, Islam sees the white-skinned and fair-haired ideal of man promoted by Western art as racial and misleading.

The second element comes from the Qur’anic verses which criticises poets as:

“As for the poets, the erring follow them. Have you not seen how they wander distracted in every valley? And how they say what they practice not? (Qur’an 26:224-26).

This formula regulates the approach of artists, writers and professionals. Islam only approves work from

“those who believe, do good work, and engage much in the remembrance of Allah” (Qur’an 26:227).

With this background, the artist’s work was guided by this criterion and was always connected to the remembrance of God whether it was in ceramics, textile, leather or iron work or wall decoration. The ways this remembrance was expressed was, of course, many. Artists worked with many different materials, from ceramic to iron, and their artistic style took many forms, such as Arabesque designs, geometrical patterns and calligraphy.

The third decisive factor dictating the nature of art in Islamic culture is the religious rule that discourages the depiction of human or animal forms

[6]. The presence of this rule is due to a concern that people would go back to the worship of idols and figures, a practice that is strongly condemned by Islam. In the early days of Islam, sculpture and imagery were seen as reminders of the despised idolatrous past. Today, the majority of Muslims still respect this rule and their attitude extends to dislike the excessive “body worship” practised in the West. The latter can be seen in the revival of Islamic dress among educated Muslim women and in their avoidance of the excessive use of make-up.

Furthermore, Islam is free from metaphysical arguments such as those relating to the trinity, the true nature of Christ, the Holy Spirit and saints hierarchy, as found in Christianity. Consequently, there was no need in the mosque for apses, transepts, crypts as well as images and sculptures of saints, angels and martyrs that played a prominent part in didactic art in Christian churches. Nevertheless, there were some instances where human and animal forms were used in Islamic art, but these were mainly found in secular private buildings of some princes and wealthy patrons. Discoveries made in the Qasre Amra palace, built by the Umayyad Caliph Al-Walid I (705-715) in the Jordanian desert, revealed large illustrations of hunting scenes, gymnastic exercises, and symbolic figures. The most important of these were illustrations depicting the main enemies of Islam, Kaisar (the Byzantine Emperor), Roderick (the Visigoth King of Spain), and Khosrow (the Emperor of Persia). There was also an illustration of the Negus, the Abyssinian king, who gave the Muslims refuge when they were being prosecuted in Mecca in the early days of Islam

[7] (Creswell 1958, p.92).

In relation to the depiction of animal forms, many examples were discovered. Lions and eagles, for example, were found in illustrations of hunting scenes, and carved in sculptures and heraldic emblems. These emblems were transmitted by the Crusaders to Europe where they were widely copied.

Islamic art differs from that of other cultures in its form and the materials it uses as well as in its subject and meaning. Philipps (1915), for example, thought that Eastern art, in general, is mainly concerned with colour, unlike that of western art, which is more interested in form. He described Eastern art as feminine, emotional, and a matter of colour, in contrast to Western art which he saw as masculine, intellectual, and based on plastic forms which disregarded colour. Of course this reflected Philipps’ cultural and artistic bias. Art in Islam never lacked intellectualism even in its simplest forms.

The invitation to observe and learn is found in both revealed and hidden messages in all its forms. Bourgoin (1879), on the other hand, compared the art forms of Greek, Japanese and Islamic cultures and classified them into three categories involving animal, vegetal, and mineral respectively. In his view, Greek art emphasised proportion and plastic forms, and the characteristics of human and animal bodies. Japanese art, on the other hand, developed vegetal attributes relating to the principle of growth and the beauty of leaves and branches. However, Islamic art is characterised by an analogy between geometrical design and crystal forms of certain minerals. The main difference between it and the art of other cultures is that it concentrates on pure abstract forms as opposed to the representation of natural objects. These forms take various shapes and patterns. Prisse (1878) classified them into three types, floral, geometrical and calligraphic. Another classification was suggested by Bourgoin (1873) involving ornamental stalactites, geometrical arabesque, and other forms. For our decorative interest, we concentrate on the three forms suggested by Prisse, which appear, either alone or together, in most media, such as ceramics, pottery, stucco or textile.

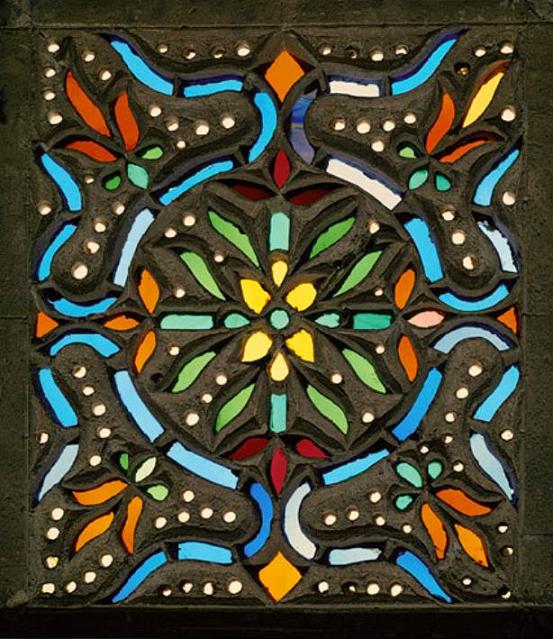

![Introduction to Islamic Art]() |

Figure 1: Detail of a floral decoration in the Dome of the Rock Mosque. |

Although, Muslim art was not, of course, developed independently of influences from nature and the environment, their representation was abstract rather than realistic, as in Western art. This is seen clearly in vegetal forms where plant branches, leaves, and flowers were woven and interlaced into and often not distinguished, from the geometrical lines around them as seen in the arabesque. The use of vegetal forms in Islamic art is also conditioned to some extent by the Islamic prohibition of the imitation of living creatures. However, this interdiction naturally decreases with the descent from human to animal to vegetable forms. Art critics describe the floral depictions and ornaments of the artists of Islam as conventional; lacking the effects of growth and the creation of life (Dobree 1920). In their opinion, the reason behind the absence of growth was due to the natural environment of the Muslim countries, where the experience of spring, the season of plant growth is fleeting. However, the religious prohibition mentioned above was behind the absence of lifelike creation in much of the Islamic floral art.

![Introduction to Islamic Art]() |

Figure 2: Illustration of a tree in a landscape decoration in the Umayyad Mosque in Damascus. |

In the Dome of the Rock and the Umayyad Mosque of Damascus, which contain the earliest examples of Islamic vegetal art, we find more realistic depictions of plants and trees, but these examples, as noted earlier, are regarded as Byzantine work for the Umayyad patrons. In contrast, the vegetal decoration in Samarra Mosque (Iraq) shows how artists, in contrast, deliberately reproduced the vine leaves and branches in an abstract form. However, by the 13th century a more realistic approach gradually gained ground in Muslim Persia and Turkey, influenced by the Chinese and the Mongols (Al-Ulfi, 1969, p.114).

The Muslims used foliage with great delicacy especially around the arches and windows. The stucco borders used in the mausoleum of the Ayyubid Sultan Qalawun, built in Cairo (Egypt) in 1284/85, consisted of buds and leaves arranged in a continuous scroll pattern. The mausoleum also contained examples of other floral illustrations set in rectangular and circular panels, a feature which became particularly popular in the 15th century (Poole, 1886). The use of this type of art extended to many ornamental objects, such as pottery, and wood and leather carving as well as coloured tiles.

The second element of Islamic art involves geometrical patterns. The artists used and developed geometrical art for two main reasons. The first reason is that it provided an alternative to the prohibited depiction of living creatures. Abstract geometrical forms were particularly favoured in mosques because they encourage spiritual contemplation, in contrast to portrayals of living creatures, which divert attention to the desires of creatures rather than the will of God. Thus geometry became central to the art of the Muslim World, allowing artists to free their imagination and creativity. A new form of art, based wholly on mathematical shapes and forms, such as circles, squares and triangles, emerged.

The second reason for the evolution of geometrical art was the sophistication and popularity of the science of geometry in the Muslim world. The recently discovered Topkapi Scrolls

[8], dating from the 15

th century, illustrate the systematic use of geometry by Muslim artists and architects (see Gülru, 1995). They also show that early Muslim craftsmen developed theoretical rules for the use of aesthetic geometry, denying the claims of some Orientalists that Islamic geometrical art was developed by accident (e.g. H. Saladin 1899).

This geometrical art is very much connected to the famous concept of the arabesque, which is defined as “ornamental work used for flat surfaces consisting of interlacing geometrical patterns of polygons, circles, and interlocked lines and curves” (Chambers Science and Technology Dictionary 1991).

![Introduction to Islamic Art]() |

Figure 3: Floral Arabesque covering the interior of the dome of Masjid-i Shah Mosque, Isfahan (16111616). |

The arabesque pattern is composed of many units joined and interlaced together, flowing from each other in all directions. Each unit, although it is independent and complete and can stand alone, forms part of the whole design; a note in the general rhythm of the pattern (Al-Faruqi 1973). The most common use of arabesque is decorative, consisting mainly of a two dimensional pattern, covering surfaces such as ceilings, walls, carpets, furniture, and textiles. From his study of 200 examples, Bourgoin (1879) concluded that this style of art required a considerable knowledge of practical geometry, which its practitioners must have had. In his view, the arabesque design is built up on a system of articulation and orbiculation and is ultimately capable of being reduced to one of nine simple polygonal elements. The pattern may be built up of rectilinear lines, curvilinear lines, or both combined together, producing a cusped or foliated effect. It is reported that Leonardo da Vinci found Arabesque fascinating and used to spend considerable time working out complicated patterns (Briggs, 1924, p.178).

Arabesque can also be floral, using a stalk, leaf, or flower (tawriq) as its artistic medium, or a combination of both floral and geometric patterns. The expression embodied in its interlacing pattern, cohesive movement, gravity, mass, and volume signifies infinity and produces a contemplative feeling in the spectator leading him slowly into the depth of the Divine presence (Al-Alfi 1969). Dobree (1920) explained the impact of Arabesque art as follows:

“Arabesque strives, not to concentrate the attention upon any definite object, to liven and quicken the appreciative faculties, but to diffuse them. It is centrifugal, and leads to a kind of abstraction, a kind of self-hypnotism even, so that the devotee kneeling towards Makkah can bemuse himself in the maze of regular patterning that confront shim, and free his mind from all connection with bodily and earthly things” (quoted in Briggs1924, p.175).

It is clearly evident that much of the credit for the development and the popularity of geometrical art goes to the artists of the Islamic world, although its origins are still debated. Claims have been made that primitive geometrical decoration was used in Ancient Egypt as well as in Mesopotamia, Persia, Syria, and India. The star pattern, for example, was widely used by the Copts of Egypt (Gayet, 1893), but the artists of the world of Islam were its all time masters.

![Introduction to Islamic Art]() |

Figure 4: Kufic Lettering (from Al-Jiburi, 1974). |

The third decorative form of art developed in Islamic culture was calligraphy, which consists of the use of artistic lettering, sometimes combined with geometrical and natural forms. As in other forms of Islamic art, Western scholars attempted to relate calligraphy to the lettering art of other cultures. The decorative use of letters in both China and Japan seem to be an area of interest to them. Theories claiming that the development of Islamic calligraphy was influenced by the Chinese, dubiously based on the pottery found in old Cairo (Al-Fustat), seem to be absurd (Christie, 1922). The lack of any substantiated proof is clear evidence as are the wide differences between the two languages in the way and the direction they are written. The suggestion of any link between Islamic calligraphy and ancient is also inconceivable. It is true that the ancient Egyptians widely used hieroglyphics on wall paintings, but these had no decorative purpose (Briggs 1924, p.179).

![Introduction to Islamic Art]() |

Figure 5: Kufic calligraphy combined with floral and geometrical decoration with intersecting horseshoe arches. Plate on Cordoba Mosque façade. |

The development of calligraphy as a decorative art was due to a number of factors. The first of these is the importance which Muslims attach to their Holy Book, the Qur’an, which promises divine blessings to those who read and write it down. The pen, a symbol of knowledge, is given a special significance by the verse:

“Read! Your Lord is the Most Bounteous, Who has taught the use of the pen, taught man what he did not know” (Qur’an 96:3-5).

This indicates that the aim of Islamic calligraphy was not merely to provide decoration but also to worship and remember Allah. The Qur’anic verses mostly used are those which are said in the act of worship

[9], or contain supplications, or describe some of the characters of Allah, or his Prophet Muhammad. Calligraphy is also used on dedication stones to record the foundation of some key Islamic buildings. In this case, a man is referred to as the founder, often a Caliph or an Emir, but he was consciously described as poor to Godor Slave of God, a reminder of his position before Allah.

The second factor behind the appearance of Arabic calligraphy is attached to the importance of the Arabic language in Islam. The use of Arabic is compulsory in prayers and it is the language of the Qur’an and the language of Paradise (see Rice, 1979). Furthermore, the Arabs have always attached a considerable importance to writing, emanating from their appreciation of literature and poetry. It is reported that the Prophet Muhammad said:

“Seek nice writing for it is one of the keys of subsistence” and the fourth Caliph, Ali commented on calligraphy as:

“The beautiful writing strengthens the clarity of righteousness”

(both quotes from Al-Jaburi 1974).

In addition, the mystic power attributed to some words, names and sentences as protections against evil also contributed to the development of calligraphy and its popularisation.

Arabic calligraphy was mostly written in two scripts

[10]. The first is the Kufic script, whose name is derived from the city of Kufa, where it was invented by scribes engaged in the transcription of the Qur’an who set up a famous school of writing

[11]. The letters of this script have a rectangular form, which made them well suited to architectural use.

![Introduction to Islamic Art]() |

Figure 6: Transcript of Naskhi calligraphy by Mahmud Yazre. |

The other script of Arabic calligraphy is known as Naskhi. This style of Arabic writing is older than Kufic, yet it resembles the characters used by modern Arabic writing and printing. It is characterised by a round and cursive shape to its letters. The Naskhi calligraphy became more popular than Kufic and was substantially developed by the Ottomans (Al-Jaburi 1974).

In general, the diffusion of the Islamic art motifs to Europe and the rest of the world occurred in three different ways. The first of these was direct imitation through the reproduction of the same theme in the same type of medium. For example, an artistic theme (or themes) in an Islamic ceramic could have been reproduced in a European ceramic. There are a multitude of examples of this kind of imitation. Perhaps the most widely acknowledged ones are the many instances of copying of Kufic inscriptions in Medieval and Renaissance European art. According to Christie (1922), Kufic inscriptions in the Ibn Tulun Mosque, built in Cairo in 879, were reproduced in Gothic art first in France, then in the rest of Europe. Lethaby (1904) also attributed to the carved pattern of wooden doors in a chapel of the Cathedral of Le Puy (France), and of another door in the church of la Vaute Chillac nearby, which were made by the Master carver “Gan Fredus”. This connection is attributed to the special relationship Amalfi had with Fatimid Cairo at that time. Amalfitan traders visiting Cairo were believed to be responsible for the transmission of these motifs to Europe.

![Introduction to Islamic Art]() |

Figure 7: Tiles in the Alhambra Palace showing geometrical Decorations and Naskhi Calligraphy, Granada, Spain. |

Male (1928) found traces of Islamic influence in many religious buildings of Southern France, in the region known as the Midi. The list of Islamic motifs, which he collated from these buildings, included horseshoe and multifoil arches and polychromy. Male believed they were copied from Andalusia. Islamic influences were also traced in Westminster Abbey in London, in bands of ornaments in the retable as well as in the earlier stained glass windows (Lethaby 1904). This was not all. Motifs such as the eight pointed star, the stalactite, the Ottoman flower (tulip and carnation) and Alhambra geometrical and colour schemes are only a few items that form an essential part of most European works of art (see Fikri 1934)

[12]. In addition, it is widely held that Gothic geometrical medallions such as polyfoil, quatrefoil or the foliated square were also of Islamic origin (Marcais, 1945).

The second way Islamic art motifs were transferred to Europe was through the transposition of source or media. In this case, an Islamic theme in a particular medium was reproduced in a European work of art in a different type of medium. For example, a theme in an Islamic ceramic work could have been reproduced in European furniture, textile, sculpture and so on. Examples of this type of transfer are once again very extensive, and we cannot cover them all here. The example of arabesque must suffice. According to Ward (1967), the fertilisation of European ornamental art during the Renaissance (16th century) was at the hands of arabesque. Arabesque and other Islamic geometrical patterns invaded European salons, living rooms, and public reception halls.

![Introduction to Islamic Art]() |

Figure 8: View of Al-Azhar mosque courtyard in Cairo. |

The third way of transfer is the most difficult to explain. Here, the motif was not copied or reproduced but gradually inspired the development of a particular style or fashion of art. There is increasing evidence that Islamic art, and the arabesque in particular, was the inspiration for both the European Rococo and Baroque styles which were popular in Europe between the 16th and 18th centuries (Jairazbhoy, 1965). The Rococo style consisted of light curvilinear decoration composed of abstract sinuosities such as scrolls, interlacing lines and arabesque designs. It was developed in France in the 18th century, and later spread to Germany and Austria. The germ of this style is found in the Islamic Aljaferia Palace (also known as Hudid Palace), built in northern Spain in the 11th century, where a number of blind arches and squinches in a style very similar to Rococo decorate its small mosque (Jairazbhoy, 1973). Other examples of this early “Islamic Rococo” are found in the Great Mosque of Tlemcen, Algeria, which was built in 1136.

Baroque architecture has also been traced back to an Islamic origin. According to some sources (for example Jairazbhoy 1965), the word “baroque” is ultimately derived from the Arabic word of burga, meaning “uneven surface”, which was the source of the word barrocco in Portuguese, which meant “irregularly shaped pearl”.

![Introduction to Islamic Art]() |

Figure 9: Decorative arcade in Aljaferia showing elements that later inspired the Baroque style. |

Muslims used motifs such as curviangular arches and squinches, which characterise the Baroque style, in their decorative art as early as the 12th century. They became especially popular under the Almoravid rulers (al-Murabitunin Arabic) who ruled North Africa and Andalusia between 1062 and 1150.

![Introduction to Islamic Art]() |

Figure 10: Northern entrance of the Ulu Cami Hospital (13th century) showing a close up view of “Baroque” features. |

In addition to the above, a more complicated decorative style, consisting of a combination of multifoil arches intersecting with one another like a screen mesh, is found in the Aljaferia Palace as well as in mosques of Tlemcen (1136) and Qarawiyyin, built in Morocco between 1135 and 1143. Another example is the Ulu Cami Hospital in Divrighi, Turkey, completed in 1229, which shows a remarkable resemblance to Baroque in its ornamentation and décor, even though it predates it by four hundred years.

The main objective of this paper has been to emphasise the uniqueness of Islamic art, which was defined by religious beliefs and cultural values prohibiting the depiction of living creatures including humans. The other most important feature is the absence of religious representation. In Islam, worship is due only to God, a feature common to many cultures, although they approach it in different manners. Art critics propound the neutrality of Islamic art, which made it easily adaptable to these cultures. Due perhaps due to its geographic proximity and religious “common ground”, no other culture was more exposed to the themes and motifs of Islamic art than the European. Despite their differences, Islam and Christianity share most of their fundamental beliefs which are connected to the same God, the same origin (of the message), and sometimes the same moral message. It is not surprising that vestiges of Islamic art were repeatedly traced in major European artworks, a fact which denotes its significance in the historical development of European art.

- Al-Alfi Abu Saleh (1969). The Muslim Art, its origins, philosophy and schools (in Arabic). Dar Al-ma’arif, Cairo.

- Al-Faruqi, R. (1973). “Islam and Art”, Studia Islamica, vol. 3 7, Larose, Paris, pp. 81-110.

- Al-Jaburi, Mahmud Shukri (1974). The Birth of Arabic Calligraphy and its development (in Arabic). Library Al-shark al-Jadid, Baghdad.

- Bourgoin, J. (1873), “Les Arts Arabes”, Paris. (Cited by Briggs 1924).

- Bourgoin, J. (1879). Les Eléments de I’Art Arabe, Paris. (Cited by Briggs 1924).

- Briggs, M.S. (1924). Muhammadan Architecture in Egypt and Palestine. Clarendon Press, Oxford.

- Christie, A. H. (1922). “Development of ornament from Arabic manuscripts”, Burlington Magazine, vo. 41, pp.286-288.

- Creswell K.A.C. (1958). A Short Account of Early Muslim Architecture. Penguin Books, London.

- Dieulafoy, M. (1903). Art in Spain and Portugal. Heinemann, London.

- Dobree, B. (1920). “Arabic Art in Egypt”, The Burlington Magazine, vol.36, pp.31-35.

- Fikri, A. (1934). L’Art de Roman du Puy et les influences islamiques, Librairie Ernest Leroux, Paris.

- Gayet, A. (1893). L’Art Arabe’, Paris.

- Grabar, 0. (1976). “The Umayyad Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem”, in Grabar, 0. (1976), Studies in Medieval Islamic Art, Variorum Reprints, London, pp. 33-62.

- Grabar, 0. (1976). “Islamic Art and Byzantium”, in Grabar, 0. (I 976), Studies in Medieval Islamic Art, Variorum Reprints, London, pp. 69-83.

- Jairazbhoy, R. A. (1965). Oriental Influences on Western Art. Asia Publishing House, London.

- Lethaby, W.R. (1904). Medieval and Co. London, Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York, vol.4.

- Male, E (1928). Art et Artistes du Moyen Age. Libraxie Armand Colin, Paris.

- Marcais, G. (1945). “Le care quadrilobe: histoire d’une forme décorative de l’art gothiqueé, Etudes d’art du Musée d’Alger, vol. 1, pp. 67-78.

- Gulru, Necipoglu, et.al. (1995). The Topkapi Scroll: Geometry and Ornament in Islamic Architecture. Geny Research Institute.

- Poole, L. (1886). Saracenic Art. London.

- Prisse d’Avennes (1878). L’Art Arabe d’après les monuments du Caire. Morel, Paris.

- Read, R. (1937). Art and Society. Heinemann, London.

- Read, H. (I 949). The Meaning of Art. Penguin Books, London.

- Saladin, H. (1899). La Grande Mosquée de Kairawan. Paris.

- Rice, D.T. (1979). Islamic Art. Tharnes & Hudson, Norwich.

- Von Grünebaum, G. E. (1955). “Idéologie musulmane et esthétique arabe”, Studia Islamica, vol. 3, Larose, Paris, pp. 5-23.

- Walker, P. M. B. (editor), (1990), Chambers Science and Technology Dictionary. Chambers Harrap Publishers, Hardcover.

Footnotes

[1] Notably R. Ettinghaussen, E. Herzfeld, K. A. C. Creswell, and A. Grabar.

[2] Reigned between (685-705).

[3] Reigned between (705-715).

[4] Until the time of Ibn Zubayr, who ruled Makkah between 678-693, The Kaabah was adorned with the horns of the ram sacrificed by the Prophet Ibrahim, in place of his son Ismail. The Caliph Umar Ibn Al-Kahttab also hung there two crescent shaped ornaments from the Persian Capital, Al-Madain. Most of the successive Umayyad and Abbasid Caliphs also sent precious items to the Kaabah as gifts, to decorate the House of Allah.

[5] Read (1937), for example, talked about environmental determinism in art. He argued that there are two main approaches to artistic expression: organic and geometric. The former appears mainly in areas of natural beauty and favourable environment. In this case, the artist is more attracted to depicting beautiful landscapes, seashores, plants, animals and humans. Geometric art, on the other hand, appears in societies of harsh natural and environmental conditions such as deserts or tundra.

[6] Although no reference to their prohibition is found in the Qur’an, a number of authentic sayings of the Prophet Muhammad did forbid them. An example of this is the Hadith reported by Muslim who narrated that Ibn Abbas: “I heard the Messenger of Allah saying: ‘All those who paint pictures will be in the Fire of Hell. The soul will be breathed in every picture prepared by the man and it punishes them in Hell” (Narrated by Muslim, 3945). Muslim scholars have different views on this matter. Some of them, especially those from the Shia school of thought permit the imaging of living beings. Others, such as Mohammed Abdu, allow imagery and photography as long they do not conflict with one’s beliefs or worship. Al-Ulfi (1969) reported that he said of photography: “In general I am inclined to think that Islamic law (Shariah) does not forbid one of the best means of learning, especially if it does not conflict with the Islamic beliefs and worship” (see Al-Ulfi, 1969, p.84).

[7] It is believed that he converted to Islam. It was reported that on hearing about his death, the Prophet Muhammad performed prayers for his soul.

[8] The scrolls, thought to be a Timurid manuscript, contain 114 individual geometric patterns for wall surfaces and vaulting.

[9] Surah Al-Fatiha, for example, is particularly favoured since it is the opening of the Qur’an and is said in all prayers.

[10] From these two main styles, a number of other sub-styles emerged as calligraphers introduced new modifications to the original style. The most familiar ones are Thuluth, Al-Rakaa, Al-Diwany, Jali Diwany, and Persain.

[11] According to Al-Jaburi (1974), after the establishment of Kufa, some Yemeni tribes who knew an early form of this lettering style settled there. This style attained its complete shape under the reign of the fourth Caliph (Ali), between 657 and 661, who was a calligrapher himself.

[12] This excellent PhD thesis published by A.Fikri was devoted to the influence of Islamic art and architecture on southern France, particularly in the Auvergne region.

*Dr Rabah Saud wrote this article for www.MuslimHeritage.com when he was a researcher at FSTC in Manchester. He is now Assistant Professor at the University of Ajman, Ajman, UAE.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![medicine]()

![medicine]()

![medicine]()

![medicine]()

![medicine]()

![medicine]()

Lighthouse on an old map, shows once where it stood (

Lighthouse on an old map, shows once where it stood (

A good example of an apparently accurate drawing based on personal observation is the sketch of the famous Lighthouse of Alexandria by the Andalusian traveller, Abu Hamid Al-Gharnati . He visited Alexandria first in 1110 and again in 1117. He described the lighthouse as having three tiers:

A good example of an apparently accurate drawing based on personal observation is the sketch of the famous Lighthouse of Alexandria by the Andalusian traveller, Abu Hamid Al-Gharnati . He visited Alexandria first in 1110 and again in 1117. He described the lighthouse as having three tiers: